205.tf - 205TF – Experimenting is above all a process

Experimenting is above All a Process

Section titled “Experimenting is above All a Process”Published

2025-01-04

Author

Rémi Forte

Category

Case Study

Words

1973

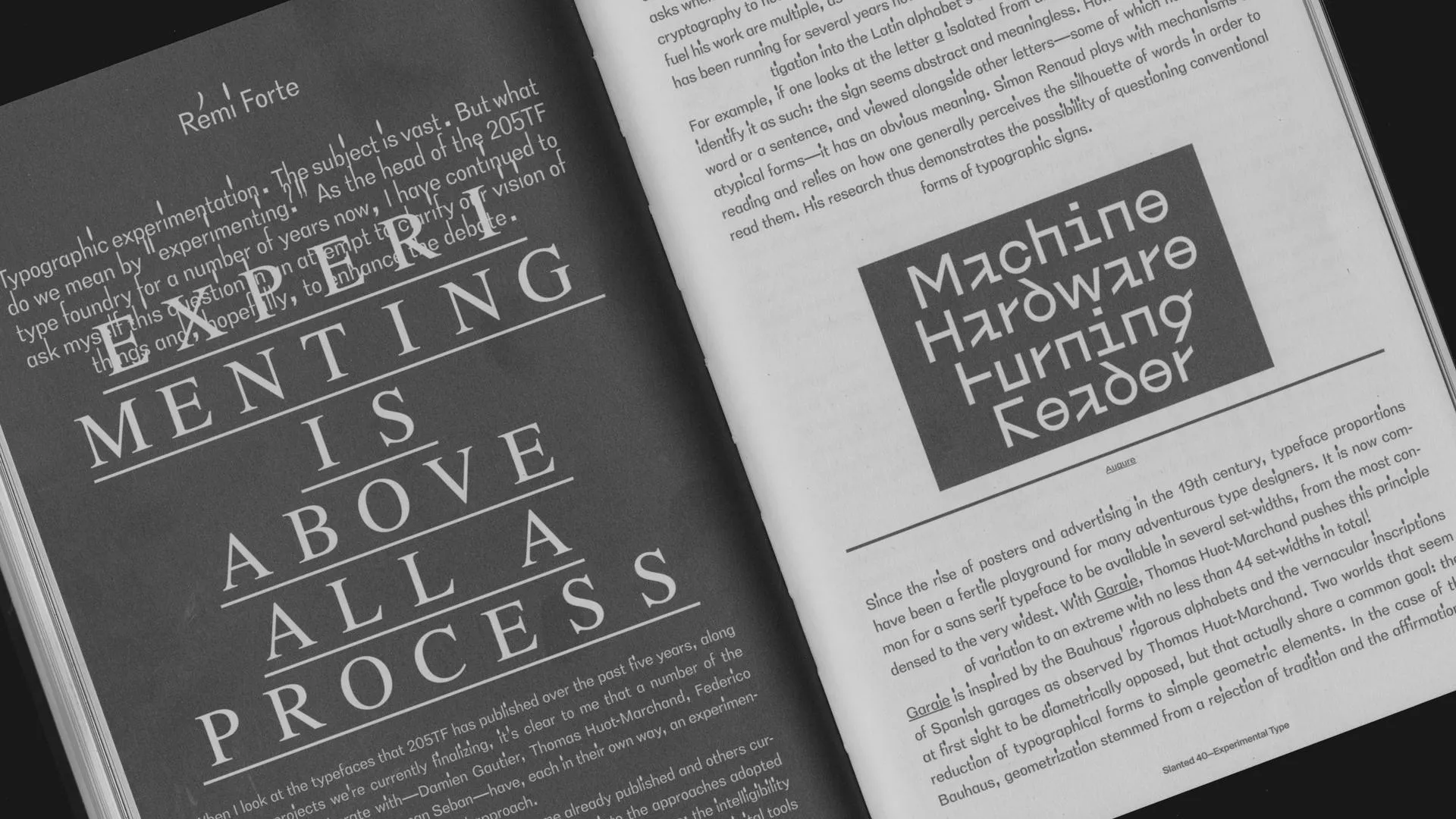

Typographic experimentation. The subject is vast. But what do we mean by “experimenting”? As the head of the 205TF type foundry for a number of years now, I have continued to ask myself this question in an attempt to clarify our vision of things and, hopefully, to enhance the debate.

When I look at the typefaces that 205TF has published over the past five years, along with other projects we’re currently finalizing, it’s clear to me that a number of the designers we collaborate with—Damien Gautier, Thomas Huot-Marchand, Federico Parra, Simon Renaud, and Roman Seban—have, each in their own way, an experimental approach.

Through the prism of a selection of typefaces, some already published and others currently in preparation, I will attempt to give some insight into the approaches adopted by their designers and the ways in which they question their technique: the intelligibility of their typefaces, how they challenge established canons, their relation to digital tools and the creative potential of their misappropriation, their take on the history of typography and its developments, etc.

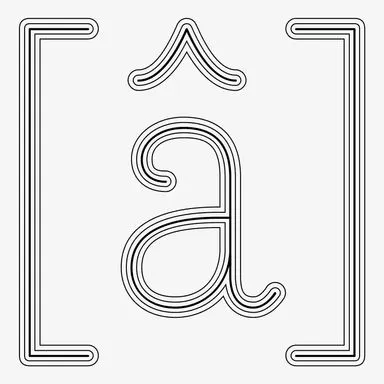

The practice of type design sometimes confronts creators with fundamental, almost existential questions. Why does the letter a look the way it does? Has it always had the same shape? Is it still possible to develop it further? These are questions Simon Renaud asks when developing a new typeface, drawing on the history of writing and methods of cryptography to nourish his type design practice. The references and inspirations that fuel his work are multiple, as can be seen on the tumblr writing-system that he has been running for several years now. The typeface Augure is the result of his investigation into the Latin alphabet’s threshold of intelligibility.

All stylistic alternates in the Augure typeface.

For example, if one looks at the letter a isolated from all other glyphs it is difficult to identify it as such: the sign seems abstract and meaningless. However, inserted into a word or a sentence, and viewed alongside other letters—some of which have equally atypical forms—it has an obvious meaning. Simon Renaud plays with mechanisms of reading and relies on how one generally perceives the silhouette of words in order to read them. His research thus demonstrates the possibility of questioning conventional forms of typographic signs.

Key “abstract” capital letters of the Augure typeface.

Since the rise of posters and advertising in the 19th century, typeface proportions have been a fertile playground for many adventurous type designers. It is now common for a sans serif typeface to be available in several set-widths, from the most condensed to the very widest. With Garaje, Thomas Huot-Marchand pushes this principle of variation to an extreme with no less than 44 set-widths in total!

Garaje is inspired by the Bauhaus’ rigorous alphabets and the vernacular inscriptions of Spanish garages as observed by Thomas Huot-Marchand. Two worlds that seem at first sight to be diametrically opposed, but that actually share a common goal: the reduction of typographical forms to simple geometric elements. In the case of the Bauhaus, geometrization stemmed from a rejection of tradition and the affirmation of an objective and rational vocabulary. For Spanish garage owners, ignorant of tradition, the reduction of letters to elementary forms was simply a question of functional logic―naïve as it might have been to reduce the design of letters to geometric forms that, for them to actually appear perfect must be optically corrected.

Yet the construction of Garaje is rigorously geometric, anchored to a scalable modular grid. And Thomas Huot-Marchand pushes this very reductive principle to its paroxysm, designing a type family made up of 44 set-widths in 5 weights, to which is added a monospace version with an even more constrained design. As if deliberately playing with the absurd, the designer has also added a last “multi” version which, thanks to a set of dynamic ligatures, make it possible to combine 15 different typefaces in the same font. With the result that Garaje offers a total of 445 variant fonts!

Design space of Garaje

While type proportions are a common issue, their vertical positioning has generally remained unexplored by type designers. Typographic compositions that play with various letter sizes are indeed the “playground” of graphic designers who, if necessary, distort and move the typefaces. Type designer and graphic designer Damien Gautier has discovered an untapped potential in this, and has developed a typeface whose height and vertical positioning can be modified by composing on a computer keyboard as if it were a piano keyboard.

Made up exclusively of capital letters, Heliuum offers several variations for each glyph. Each letter has four different heights, and the smallest version is built, thanks to a bending of the principle of conditional ligatures, on four different baselines. The user is thus free to compose titles by varying the size and position of the letters without compromising overall typographic coherence. Heliuum seems to evoke both a mechanical appearance and sophisticated design, with many of its details contradicting the initial impression of a typeface that has not been optically corrected.

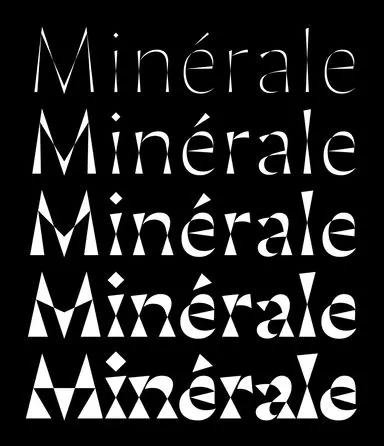

Vector drawing has become the basic tool of the type designer. Vectors are a mathematical description of the contours of letters that allow the size of a font to be increased or decreased. Thomas Huot-Marchand seeks to play with the possibilities offered by testing the limits of vector drawing. For him, it is the starting point for a new formal experimentation and for his Minérale typeface.

Inspired by the geometric and crystalline forms of minerals, Minérale has the particularity of having stems whose sides intersect in the middle. Something that is usually the sign of a design error is, in this case, the founding principle.

Beyond simply questioning the use of digital tools, thanks to its geometrical exaggeration this typeface is also a form of research into the very structure of serifs. Thomas Huot-Marchand has pushed the phenomenon of thinning the central part of the stems to its extreme: two joined triangles create a clear, almost luminous zone in the center of the letterform. The result is astonishing. Sober, even crystalline in its leanest weights, Minérale becomes exuberant in its thicker versions, approaching the silhouette of the so-called ‘Italians’ with their characteristic inverted contrast.

Minérale styles

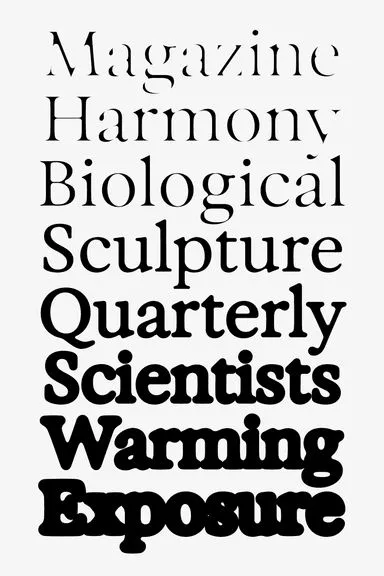

Since 2016 and the introduction of version 1.8 of the OpenType format, variable fonts have monopolized the attention of type designers. While this format is considered to be a major evolution, the use of axis variations to modify weight, width and even optical sizes is ultimately a conventional transformation inherited from the much older techniques of punchcutting. Federico Parra abandons this conventional approach to propose a new way of thinking. The typeface Exposure, initiated at the Atelier national de recherche typographique (Nancy, France), borrows the principle of exposure from photography. The question at the heart of his work is simple: how does the design of a typeface react to varying levels of exposure to light? Some may see this as a nod to another technique: phototypesetting.

The axis variation of Exposure ranges from −100 to +100 and gives one the feeling of adjusting the light intensity to which the typeface is subjected, thus affecting its contours. At zero, the typeface is sharp and clear. As the index decreases the font is increasingly underexposed. The typeface seems to deform, becoming excessively black. Counterforms are filled to the point of illegibility. Conversely, as the index increases, so does the intensity of the light. The original drawing is somehow overexposed until some parts disappear as if burnt out. Numerous intermediate designs that emerge between these two extremes have been carefully sculpted by Federico Parra: a real feat of design and technique that allows one to envisage other ways of exploiting the potential of variable fonts.

Exposure variations

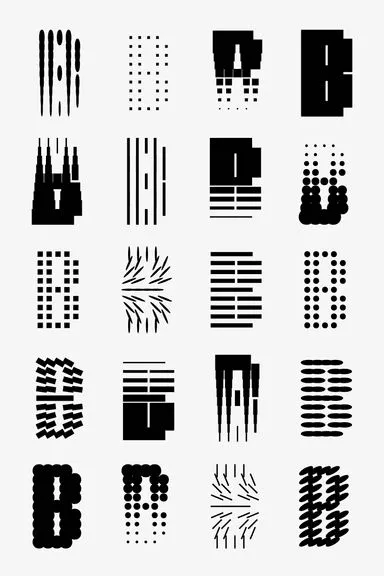

Boosted by the use of type design software and the component-based approach, the modular approach to type design has once again—100 years after the Bauhaus—become an area for experimentation.

In 1967, Jacques Bertin published his groundbreaking book Semiology of graphics: diagrams, networks, maps which providing visual tools for translating information into graphic form. The cover, designed by Dutch graphic designer Juriaan Schrofer, features lettering inspired by the very system developed by the author. Roman Seban used Bertin’s work along with Schrofer’s typographic interpretation to create a modular font with multiple axis variations.

Rigorously constructed on a grid, the structure of each letter allows for the application of different modules (circle, rectangle, cross, triangle…), creating typographic signs on the basis of patterns. These modules can be transformed according to different axes such as the shape, the size, the gradient or the orientation. Potential variations are almost inexhaustible and the result reflects the potential of the initial image, thanks to the use of variable font technology.

Bertin variations

Typographic classifications have regularly been a heated topic of debate. In spring of 2021, the International Typographic Association announced that it was abandoning the Vox-ATypI classification in an effort to design a more inclusive classification. As far back as 1980, Jean Alessandrini, a self-taught French illustrator and type designer, proposed Codex 1980, a typeface classification that he considered better adapted to the explosion of typographic standards in the age of phototypesetting.

Damien Gautier adopted this contrarian approach to begin designing a family of four distinct typefaces— simplice (sans serifs), deltapode (triangular serifs), emparecte (rectangular serifs), and emparecte with brackets (when the serifs are accompanied by a rounded form). Initially designed for a visual identity in 2011, he pursued his research in 2021, designing CX80, which finds its home in the family of “hybrids” that groups together, according to Jean Alessandrini’s classification, typefaces possessing features that are specific to a number of type families.

With each letter, the user can use the keyboard to graft serifs onto a linear frame. By dynamically associating up to four elementary forms of serifs, it allows one to exhaust all combinations of glyphs.

All possible variations of the letter A in the CX80 typeface.

Extending the work of punchcutters from the earliest days of printing, the digital type design approach usually consists of describing typefaces in terms of their outlines and their vector paths. However, designers such as Edward Catich, Gerrit Noordzij and Donald Knuth have developed an alternative approach that describes a sign in terms of its interior and its frame. This approach to type design is closer to calligraphy, which considers each sign according to its ductus and by the mark made by the tool, brush or pen.

Based on Summer Stone’s interpretation of Bodoni, Thomas Huot-Marchand developed Mononi, a mono-linear typeface originally designed as part of the visual identity of a musical theater (Besançon, France). He worked with a technology that remains little explored by typographic designers, initially conceived for mechanical engraving, and in particular for machining: single-line typefaces.

Using the structure of Bodoni, Thomas Huot-Marchand proposed to revisit a part of the history of typography and to play with it. By applying an outline to this frame, users can increase the thickness of the line and modify the typeface’s weight according to their needs.

Mononi typeface weight distribution, centered on its skeletal structure.

While all of the typefaces in the 205TF catalog are systematically intended for a variety of uses, this handful of examples shows that research and experimentation do not run counter to a desire for wide distribution. On the contrary, they manage to propose resolutely new typefaces, rather than simple variations or revivals. It is not only a question of formal experimentation, but also of experimenting with techniques and uses.

This plural and exploratory approach is based on the fact that the research is carried out by type designers who are also graphic designers who are acutely aware of the needs of typeface users and can also experiment with their limits: an asset for identifying new territories ripe for exploration. At the juncture between disciplines, they create an innovative and stimulating dialogue between type design and the use of typefaces: the effective encounter of innovation and the everyday lives of those who use typefaces.

Article “Experimenting is above all a process”, first published in Slanted — 40 Experimental Type (2023).

Featured Fonts