vaughntan.org - Good strategy understands affect, not just cognition - Vaughn Tan

Good strategy understands affect, not just cognition

Section titled “Good strategy understands affect, not just cognition”23/3/2025 ☼ strategy ☼ affect ☼ emotion ☼ cognition ☼ discomfort ☼ uncertainty

This is #3 in a series on seven tensions that lead to common misunderstandings about strategy.

Good strategy understands affect, not just cognition.

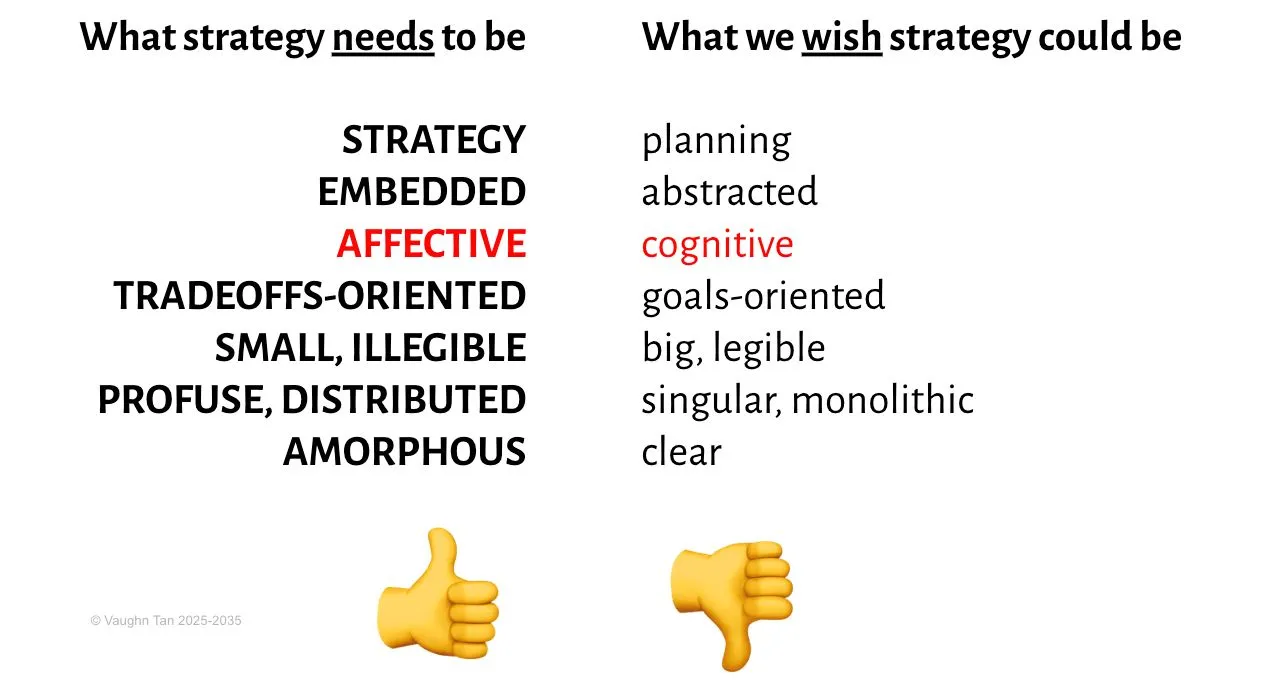

When doing strategy work, what most often gets emphasised is the highly cognitive stuff: Developing analytical frameworks, collecting data, testing hypotheses. The thinking, cognitive side of strategy-making is crucial. But paying so much attention to the cognitive work of strategy leads us to mistake strategy for being only about cognition.

In fact, for strategy to be good, it must also understand affect and how it affects cognition and action. (Affect is the experience of feelings in general, which can be quite diffuse. Emotion is part of affect and is more intense and usually directed at something specific.)

Ignoring affect creates real problems for strategy-making and implementation:

- It limits the range of scenarios considered in strategy-making. Fear and anger, or even the diffuse feeling of discomfort, make us discount or, worse, avoid thinking about unpleasant futures or aspects of the environment that strategy needs to consider and be ready for. This is bad because strategy should prepare us even for scenarios we find scary or uncomfortable.

- It makes strategy implementation harder. Strategy always requires changing how organisations work. Change unsettles, scares, and angers people. Scared and angry people resist change. If we don’t acknowledge the feelings and emotions that change provokes, execution becomes much harder—or fails altogether.

Two ways acknowledging affect makes for better strategy

Section titled “Two ways acknowledging affect makes for better strategy”Ignoring affect creates problems. But taking affect seriously improves strategy-making by:

- Expanding the set of possibilities considered, which leads to more robust and adaptable strategic choices.

- Designing strategy that increases the likelihood of successfully implementing that strategy in the organization.

Acknowledging affect improves strategy-making

Section titled “Acknowledging affect improves strategy-making”Unacknowledged affect in the strategy-making process ends up distorting strategy.

Kodak is a good example. In the 1970s, Kodak dominated the photography industry. In 1975, a Kodak engineer invented the first digital camera — but filmless digital cameras were an uncomfortable product because they were clearly antithetical to the company’s existing business in photographic film. Kodak leadership decided to avoid this uncomfortable potential line of business to continue focusing on the well-understood, comfortable film business. Rivals which didn’t find digital cameras uncomfortable entered the market, transformed the photography industry, and left Kodak behind. It went bankrupt in 2012.

A strategic and existential threat that is uncomfortable is actually one that is more important to account for in strategy-making. Acknowledging affect in strategy-making can take many forms. Here are a few of them:

- Bringing in external perspectives. Insiders are often too emotionally invested in the status quo to see its limitations clearly. Outsiders surface uncomfortable and unspoken assumptions and challenge entrenched ways of thinking.

- Interrogating goals rigorously. It’s easy to assume that existing objectives are still valid, but sometimes they need to be revised. This process can be uncomfortable, especially when it calls past decisions, vested interests, and fixed costs into question.

- Training leaders to engage with discomfort.Strategic decisions often feel uncomfortably uncertain, which is why it is tempting to avoid doing strategy by focusing only on planning. To avoid this, leaders can train themselves and their organisations to tolerate discomfort by exposing themselves to uncomfortable uncertainties in lower-stakes settings. Organisations which do this repeatedly end up more tolerant of discomfort and more likely to be able to think and act effectively in uncomfortable, uncertain situations.

Acknowledging affect in strategy-making makes it harder for organisations to avoid inconvenient but important truths and also encourages more adaptive, reality-based strategy-making.

Acknowledging affect improves strategy execution

Section titled “Acknowledging affect improves strategy execution”Affect and emotion don’t just shape the strategy-making process. They also shape the execution of strategy.

Change is disruptive. Even when a strategy is well-reasoned and necessary, it forces people to abandon familiar ways of working and do new things. Novelty and uncertainty provoke feelings of anxiety, frustration, or outright resistance. People who feel unsettled by change are less likely to support it — and more likely to slow it down or try to block it. Strategy that fails to acknowledge these kinds of responses is much harder to successfully implement.

Some approaches to strategy that acknowledge affect include:

- Writing strategy in language that makes sense on the ground. If a strategy isn’t understandable or relatable at the implementation level, resistance is inevitable.

- Breaking big strategic moves into many small, low-stakes changes. Large, abrupt changes trigger fear. Smaller, incremental steps feel more manageable and less threatening.

- Building strategy from the ground up rather than imposing it top-down. People are more likely to embrace change when they’ve been involved in shaping it.

These approaches are part of what I call “ sneaky strategies.” Unlike big, top-down strategic plans that look great on boardroom slides but get stuck in execution, sneaky strategies work by avoiding friction and slipping past organizational defenses.

They’re effective because they acknowledge how affect shapes peoples’ actions and reactions. Instead of triggering fear, anger, or resistance, their aim is to make change feel tolerable, natural, or even invisible. They work with, not against, the realities of how people and organizations respond to disruption.

Good strategy understands affect

Section titled “Good strategy understands affect”Strategy isn’t just about cognition: The best strategy-making accounts for affect too. Doing this improves strategy in two critical ways:

- It expands the range of scenarios we consider, leading to better strategy-making.

- It reduces unnecessary resistance to implementing strategy.

Strategy that ignores affect struggles to work in practice. Strategy that acknowledges affect is both better and easier to implement.

Get in touch if you’d like to chat about making this type of strategy work for your organisation.

I’ve been working on tools for learning how to turn discomfort into something productive. idk is the first of these tools.

And I’ve spent the last 15 years investigating how organisations can design themselves to be good at working in uncertainty by clearly distinguishing it from risk.