substack.com - How to craft a political message

What the Labour Government Can Learn from a Prime Ministerial Fax from 25 Years ago

Section titled “What the Labour Government Can Learn from a Prime Ministerial Fax from 25 Years ago”

This particular note was faxed from Chequers, the Prime Minister’s country residence, at 17.32 on 21st April 2000. I know, because faxes record the date and time at the top.

Yes, in those days it was government by fax, not WhatsApp. On a Sunday evening we would wait for the dial-up sound of the fax machine - the ping and the high-pitched screech - as the note from Tony Blair began to drop. These were his weekend reflections that would provide the agenda for the 9am strategic meeting we had in his ‘den’ at Number 10 every Monday morning.

For those too young to have experienced it, and that doesn’t include NHS workers who were using fax machines until very recently, (some, I’m sure still do!) the paper that spewed out of the machine was that plasticky - shop-receipt-quality stuff - and it continued rolling out, a 10-page document in one long sheet, several metres long.

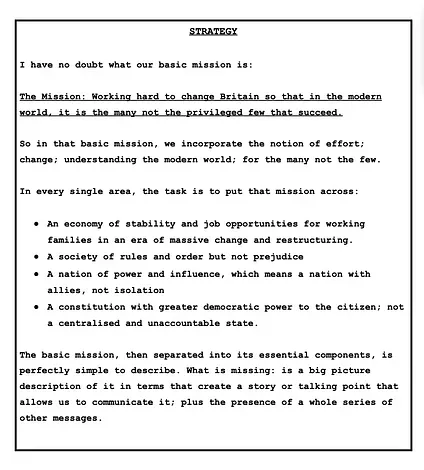

Anyway, enough of the antiquated fax machine. This Prime Ministerial note was almost exactly three years into the Labour Government and the first page read: (I have kept the underlining)

That is the end of the first page of the fax. Unfortunately, and tantalisingly, I do not have the rest of the note. I have kept many from the New Labour days but I am, to say the least, not the neatest filer of paperwork.

But like an archaeologist piecing together the fragments of ancient hieroglyphics, I will attempt to use this single page from April 2000 to illuminate the message challenge faced by the current Labour government. And given that Number 10 has just appointed new people to the communications team, this is a good time to rethink how message is developed.

The first thing to note from the memo, is that any politician - in this case Tony Blair - who writes: “I have no doubt…..” is reflecting the fact that within the office - and the country - there is quite a lot of doubt.

The fact that Tony Blair was writing this note three years into his first term shows how difficult it is for any government to define itself given the messiness of events. Some see that period as a model of clarity and certainty. Those of us who were there at the time know that wasn’t always the case. Yes, there was a general sense of direction. But we agonised repeatedly and exhaustively over exactly how to express our mission for the country. Keir Starmer is today getting a lot of grief for a lack of clarity one year into government. Blair was getting the same after three years.

The Joys of Iteration

Section titled “The Joys of Iteration”The other important lesson, which I don’t think is heeded enough, is that political strategy and message is iterative. It requires debate, argument and a lot of thinking. In the Blair government, there was an ongoing dialogue about the big political questions. All of us, striving to get to greater clarity, to deepen and strengthen the central arguments. This process can seem, and I think Starmer sees it this way, as endless navel-gazing - dancing on the head of a pin, banging on about abstract nouns or rarefied concepts; wasting time that could be spent on the actual doing. And at times it certainly seemed like we were going round in circles. But all of us knew it really mattered.

It mattered because the Cabinet, backbenchers, civil servants, civil society need to know what is driving decision-making, what it’s all for and what matters most. Strong message can motivate and connect to people emotionally, (and I will write more on this in future posts) and crucially it gives the public a reason to stick with you - the higher purpose - when times are hard or when a government makes mistakes.

Leaders need to explain the why, the what and the how of their project. And the why needs to be explained three or four times more often than anyone thinks is necessary - because it needs to cut through a lot of noise.

There are three tiers to political message.

- The top tier - the mission, the why, the ‘what does it all add up to?’

- The middle tier - much neglected and key to winning political arguments, it is the conceptual underpinning of each policy area. For example, what is Labour’s approach to growth, NHS reform, welfare reform etc?

- The retail tier - what does this mean for voters? What benefits will they get? How will it make people feel?

The top Tier of Message: the why

Section titled “The top Tier of Message: the why”Let’s look some more at the central mission statement - the top tier - in the Blair note: the why.

The Mission: Working hard to change Britain, so that in the modern world, it is the many not the privileged few that succeed.

This simple - admittedly slightly clunky statement - has several crucial elements: The creation of a new Britain through change. A sense of whose side we are on: ‘the many not the privileged few’. And a reference to modernisation - ‘the modern world.’

An example of iteration - one that lasted the entire 10 years of the Blair administration - was the ongoing debate between the ‘many not the few’ camp and the ‘for everyone’ camp.

The ‘many not the few’ advocates were those who believed that message, and indeed politics, needs enemies - who you are for and who you are against. We are for the many and against the few. And we define the few, often in colourful terms, to make the point.

The ‘for everyone’ advocates were those who believed in a ‘big tent’ strategy. We don’t want to put off anyone from being part of the project. We want to support business and trade unions; tax breaks for entrepreneurs and better rights for working people. Parties of the Left often exclude people who are not seen as principled enough. A ‘big tent’ strategy is an acknowledgement that to win elections you need millions of votes, so alienating large sections of the public is unwise.

In the New Labour period, Gordon Brown used to advocate a ‘many not the few’ position and Tony Blair the ‘everyone’ position. And the creative tension between the two was usually helpful. But it wasn’t black and white as the underlined mission statement above shows. This note is a rare example of Blair championing ‘many not the privileged few’. I remember him thinking during this tough mid-term period of the first term, that he needed more cut-through - something edgier - to gain greater definition and debate.

I happen to think his best Labour Party Conference speech did exactly that. His ‘forces of conservatism’ speech delivered in 1999 painted a vivid picture of those on the Left and Right who throughout British history had stood in the way of change. But Blair never wanted a hard-edged message to go too far and was uncomfortable if he thought sections of society, particularly business, were being demonised.

The current bind for the Labour Party is this. Right-wing populists are using ‘enemy’ based messaging incredibly effectively. Targeted at both illegal immigrants and metropolitan elites, they make the case powerfully for why the country is in a mess. Labour currently lacks confidence in defining its enemies. It has of course made quite a few inadvertently: the elderly (winter fuel), the disabled (PIP payments), farmers (inheritance tax) and business (National Insurance).

In its second year in office it needs to be clearer who it’s fighting for, and crucially who it is against.

The main point here is that debating these message questions, at length, pays off. It is the route to clarity and a greater sense of direction.

The most notable example of us doing this for Starmer in Opposition was the time we spent, as advisors, debating the age-old question of what we call the voters we are speaking to. You will see in the first bullet point in the Blair note, the phrase ‘working families’. The Starmer formulation was ‘working people’. Families sound warmer. People can appear more inclusive; what if you don’t have children? The big debate was about whether ‘class’ had made a comeback. Was Labour’s loss of Red Wall seats because it was out of touch with its roots, that it no longer spoke for the working class? In this age of insecurity is it powerful to talk of ‘the working class’ and ‘breaking the class ceiling’? Would that show that Labour got people’s struggles?

Like in the Blair/Brown days, two camps formed. One who believed that Keir’s story was a great example of breaking the class ceiling, being born working class and fighting his way into the middle class - and so we should unashamedly use that language. The other camp believed it could too easily be portrayed as ‘class war’ and put off crucial middle class voters. Journalists picked up on these tensions, by trying to find differences between senior politicians in how they defined ‘working people’. Personally, I prefer “working families’ to ‘working people’. And I believe ‘breaking the class ceiling’ has real punch and gives a dynamic sense of fighting ‘for the many not the few’.

One more thing to note from the main message in the Blair memo is the phrase ‘in the modern world’. Modernisation was key to the Blair project, as was the future. It is absent from much of the current government’s message. Yet we know Labour does best when it ‘glimpses’ the future and paints a picture of how, through radical change, a better life will emerge.

So what might the mission statement - the why - for the current government look like?

I would be asking the following questions:

- How do we show we are preparing Britain for the future? (Something that would immediately give Labour an advantage over the other parties, including Reform)

- How do we show whose side we are on?

- How do we show that we are actively trying to change the country?

- How do we tap into people’s hopes and aspirations not just insecurities?

This is the sort of mission statement that might begin to capture these ideas, and which should be the subject of proper deliberation.

Mission: To equip working families with the tools, opportunities and fair chances to thrive -not just survive -in a fast changing world, breaking down the barriers that stand in their way.

Working families describe who the government is for.

My preference is for a message of hope - how we will give people tools and opportunities to thrive.

Fair chance taps into a more emotional and deeper feeling many have, that they are not getting the breaks and the system is rigged against them.

Moving from surviving to thriving is the vital shift that is at the core of what Labour must offer. But it acknowledges that many are just surviving - so it gives a sense of the foundations of security that people need to build on.

Breaking down the barriers reinforces the urgent, hands-on nature of the reforms.

To be clear, this mission statement is a piece of positioning. It is for the communications team to turn it into punchy products and slogans. Blair says as much in the last paragraph of his note.

The Middle Tier of Message: the what and the how

Section titled “The Middle Tier of Message: the what and the how”What this note also reveals is the importance of what might be called the middle tier of message. If the Mission statement is the top tier - the overall narrative - the middle tier is the conceptual underpinning to each policy area.

This middle tier of message is vital, particularly if you are making controversial policy changes.

The most famous of these from the Blair era and missing from his note is ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime.’ This has sometimes been mistaken for a superficial slogan. It is in fact a piece of brilliant positioning. The phrase forces policy makers and politicians to consider both tough action on crime and policies to prevent crime. It means that an individual must be held responsible for their actions, something many Labour politicians didn’t advocate at the time. And, at the same time, demands action to tackle poverty and lack of opportunity that create the conditions for crime. It is a balanced argument and one that chimes with the views of the public.

In the Blair note the middle tier message comes in the bullet points. When Blair writes: “A society of rules and order but not prejudice,” he is also positioning the government to do two things simultaneously: promote gay rights eg civil partnerships and crack down on antisocial behaviour. Blair’s belief was that people were tolerant of how others lived their life, but intolerant of those who made life misery for others.

Today, the government needs position statements on all the key areas where it is battling to make change. Their absence is one of the main reasons why things have been so rocky.

On welfare reform - what sums up the policy? Is it the same or different from the one we had in the Blair days: ‘Work for those who can, security for those who can’t.’ This statement meant we would protect and indeed give extra help to those who would never work, while doing everything we could to get those who were capable of working back into employment.

On NHS reforms, the three shifts are clear: from hospital to community, treatment to prevention, analogue to digital. But what is the summing up of the new NHS operating model?

On the economy, what is the distinct, conceptual way of describing the growth strategy?

Very often the process of forming these middle tier messages unearths weaknesses or lack of clarity in the policy itself and so is a good forcing mechanism for improving it.

The Retail Tier of Message: ‘the Offer’

Section titled “The Retail Tier of Message: ‘the Offer’”The Blair note does not include the retail tier of message. Or at least the one page I’ve kept doesn’t. But it is worth noting its importance.

Message is an edifice. If you go straight to the retail, without the first two tiers, as some politicians would like, then voters see through it. They think you are pandering and haven’t got the substance. The pledge to put ‘more bobbies on the beat’ often falls foul of this. The public may want it, but they also know that politicians always promise it, and they have learnt to take these kinds of promises with a healthy dose of scepticism.

A retail offer to voters needs to be symbolic of a wider argument.

For example, voters need to know first that you are going to be ‘tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime’ and then they will understand that tougher sentences is a policy example of tough on crime and more youth hubs is an example of tackling the causes of crime.

Every retail message needs to include: a) a benefit to voters (including how they will feel) b) a specific change c) how you are paying for it. We are cut waiting times for children from a year to six months, paid for by savings from abolishing NHS England, so that anxious parents have peace of mind that their children will get the faster care they need.

The Three Tiers Need to Be Planned together

Section titled “The Three Tiers Need to Be Planned together”The three tiers of message need to be worked on holistically in each of the different departments of government with Number 10 bringing the thinking together in a coherent whole. The lead politicians need to shape it and own it. They need to devote structured time to it. It can’t be outsourced because they need to weave it into every speech, every video, every interview, every Parliamentary statement. It is one of the big pieces missing from Labour’s first year and essential it is done properly in its second.

Politics is a craft. Political strategy and message are part of that craft. It is a craft that requires discussion and deliberation. Getting it right is the difference between a government adrift and one that has a clear direction and is able to win each political battle - lining up the arguments, and boiling them down into clear pieces of communication.

That fax, spewed out noisily all those years ago, was just one example of the endless and vital quest - the lifeblood of politics - to explain what you are doing and crucially why you are doing it.