Sam Schillace's Sunday Letters

The Changing Nature of Collaboration

Section titled “The Changing Nature of Collaboration”

Working together is a fundamental part of the professional world, at least for most types of informational work. Anyone who has been part of any kind of company knows that learning to work with other people is a critical skill. Not having this ability usually is a real limit in how successful you can be. Students know this too - even though they’re in competition at some level (for grades and placement), students spend a lot of time formally and informally working together, which is good. AI tools are going to change the nature of this collaboration.

Why do we collaborate? There are fundamentally two reasons, and we can label them quantity and quality. Quantity is simple - it means “there is too much work for one person, let’s spread it out”. Quantity means “you have some information or skills that I don’t have (or vice versa), working together will make the outcome better/faster”.

Right now, we are just starting to get LLM-based tools that can act independently and reliably (people call these agents, but I like to think of them as tools - I don’t find it helpful to anthropomorphize). These tools are starting to be more and more reliable though, and it’s more possible to hand work off to them. Soon, they will be able to spin up copies of themselves if they want to work on a task in parallel. This chips away at the quantity problem - humans don’t “scale up”, but computers do. So, suddenly, we don’t need to work with a big team to do some kinds of big tasks.

This has really interesting side effects. One of the core ideas in the software world is the “mythical man month”, which comes from an old book of that title. It’s the observation that, for software (and other knowledge work teams), scaling up doesn’t always work, because communication overhead increases as the square of the team size (everyone has to talk to everyone else if you aren’t careful). But with AI agents who can coordinate or be coordinated on a large task, this problem starts to go away - a smaller number of human engineers can be much faster, because they don’t have to communicate as much to get work to happen.

Quality, our other reason for collaborating, is more complex. LLMs absolutely bring skills to the table, so in some cases, you can get higher quality “collaborating” with an LLM instead of a person. Not always - the information and context can often be as important or even more important. As LLM systems know more for us and are able to share more of it under our control, this will change too.

Is this change to collaboration good or bad? Yes! It will probably be some of both, as all things are. The good is that more people are empowered to do more work for themselves - I am always a believer that removing barriers to human imagination and energy is a fundamentally good thing (as long as we have good humans). Making it so that someone who might not have been empowered to be ambitious now is, seems pretty great to me.

On the other hand…we need to get along with each other. Working together is an important skill to have. It would be a shame to lose that. I suspect that what will really happen though (and I am seeing it in my own teams) is that we will actually find ways to work together more with the help of AI. People like each other, for the most part. We want to work together and we find ways to do it. My engineering team spent a little bit of time happily coding alone, and then very quickly started to look for ways to work together, share context, and continue to amplify each other.

I’m optimistic. But whether you are or not, it’s clear to see - collaboration is going to change, a lot.

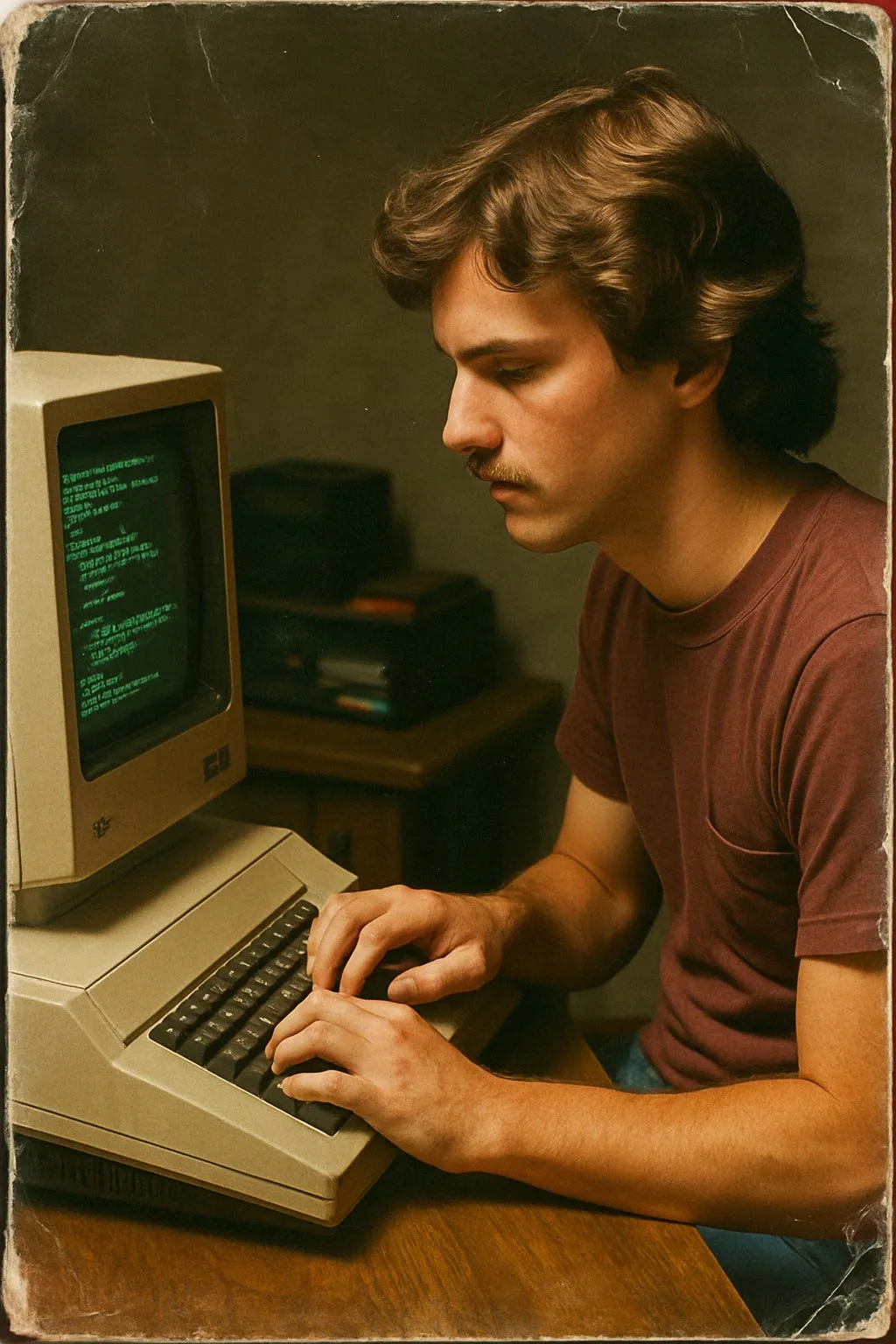

Code Goes First

Section titled “Code Goes First”A Peek into the Future

Section titled “A Peek into the Future”

Gemini likes to add text from the blog post, I guess.

Usage of generative AI is uneven, and I still know lots of folks who don’t do anything much with it. Even a lot of coders are still skeptical or are only using it as an autocomplete tool, not really getting much done. But there are many more advanced coders who are getting really astonishing amounts of work done, using new mindsets and new tools. I want to argue that this isn’t an anomaly - it’s foreshadowing of how all knowledge work will look soon.

Why would code go first? Code is well suited to LLMs - it’s all text, it’s mostly online so there is a lot of it to train on, the structured nature of it makes it tokenize well, and coding tools are already very command line oriented, which means the plumbing to move code and code actions and artifacts around is already well developed. This last is possibly the most important part - code is just easier for an LLM to work with.

But that plumbing is being built out for other knowledge work. There are new protocols, like MCP, being implemented now that will allow any program to be connected in an LLM friendly way. As more work happens with them, there will be more training data, and more best practices. Work on code will inform this but there will also be new inventions in other fields. And finally “a group of people working in a code repository with tools and artifacts that are both primary and synthesized” is topologically identical to “a group of people working on a project in a directory with artifacts they author and generate”. The only real difference is the nature of the artifacts, and some nice things about code, like change management, that might cross over.

So if code goes first, what is going on with code right now?

With the best coders, the approach is something I think of as “recipes”: combinations of code, system prompt and normal prompting that are capable of targeted, long-term processes. Usually these recipes have “metacognitive” guidance - a fancy way for saying that these are strategies for the models to observe itself, iterate and correct (some) errors during these long processes. This means that very complex things are getting done regularly.

Here are some examples, actually which aren’t coding (showing that this is starting to bleed over). I have a researcher working with me who has now written two papers, each in less than 6 hours, each of which involved a software design, external research, running an experiment (one on multiple LLMs, one a survey using mechanical turk), creation of software as a result and the writing (and formatting in LaTEX) of a formal paper. This wasn’t one single prompt (“go do this for me”) but it was a series of fairly complex tasks given to the models in parallel, while other things were worked on.

Two other personal examples: I needed to write a new chapter for my book, and I wanted to update on the past year. So, I asked a long-running agent to read the book (9 seconds! That’ll boost the ol’ ego), read the last 50 of these letters, look for themes, pick 10 letters that represented those themes, and write a 1000-word header for the chapter, and then append the 10 letters. This ran successfully in the background in 20 minutes or so. Another (silly) example: I gave an agent a picture of a broken drawer in my refrigerator, and a picture of the serial number/model card and told it to go find a place I could buy a replacement. First try, no problem.

(There are many, many coding examples that I’m seeing as well, and often they are more impressive than those examples, but they’re harder to understand for a non-technical audience, and longer to explain anyway)

There is a quiet, radical revolution going on in the coding community. I believe it will start to spill over soon into other information work. The examples above use the same techniques the coders are using, but in the consumer realm. We are starting to understand best practices, and we are starting to have models that are now capable of performing them accurately. Right now, the tools are a bit too rough and obscure for non-coders to easily use, just like every new technical wave is at first. But that won’t last long.

Code goes first but it won’t be the last.

The Amazon of Thought

Section titled “The Amazon of Thought”Value Isn’t Always what You Think

Section titled “Value Isn’t Always what You Think”

There is a debate going on right now about whether AI is “worth it” for various tasks. I wrote about this last week, and it’s been on my mind again this week. This time, let’s look at some anecdotal signals instead of trying to derive from first principles.

When Amazon first appeared, there was a lot of debate about the value of ecommerce. No one was really used to it, shipping and returns were hard, logistics was unsolved, and so on. I remember reading lots of very serious articles on how the economics would never work, and indeed, the companies that implemented it poorly (hello Pets.com) failed.

But Amazon started out with what seemed like a really smart premise: we’ll give you access to every book published. In the modern age of streaming, kindles and all kinds of online content, this doesn’t seem that useful, but in that era, when bookstores were a disorganized mess, hard to search, inconvenient to get to, and slow to order from, it was a real improvement1. And whether or not the economists and pundits recognized that value, end users did, and it powered that business.

You could think of LLMs as “Amazon, but for thought”. Suddenly you have access to, more or less, all of the thinking, in one convenient place. Experts and pundits can talk about whether that’s really more efficient, but users are speaking, and I think there is real value there, whether it’s “officially” captured or not.

Here are my anecdotes: the lead engineer on one of my teams is currently spending about $200 a day in inference costs to do his job, and they’re (to my eye) much more productive than before. We don’t regret the spend and are looking for ways to usefully increase it.

A good friend is a professor at a local university estimates that they spend roughly $500 a month on one of the AI services to help with their research - and they are doing things they couldn’t or wouldn’t have done before. I don’t know of any other service where anyone I know spends like that!

And the pattern of “I get to do a new thing” is showing up in other places. I have “non-technical” people producing ideas and prototypes they wouldn’t have before. It’s hard to measure the productivity of that, because you’re dividing by 0.

I don’t really have much direct insight but I don’t know of any big company or datacenter that has “too many” GPUS right now, or even any that aren’t utilized. As far as I can tell, everyone is using it as fast as they can build it.

And there definitely seems to be some kind of “Jevon’s paradox” going on - token cost came down 100,000X over the past few years but usage has gone up even faster. That’s bad if you were depending on the reduction in cost to fix a margin problem, but really good if you are trying to understand market demand. It’s not surprising - as the models get smarter, we use them. Who wants the dumber assistant?2

The last two times this happened were the internet buildout, and the mobile one. I remember the exact same feeling - we almost couldn’t build capacity fast enough to satisfy demand. If anything, AI adoption is more rapid.

Value isn’t always crystal clear. It’s easy to measure a decrease in cost or time - but that kind of “value add” isn’t really interesting in the long run, because you can’t get below 0. What is interesting is new value. But what is that? We watch a lot of content that would have been thought to have no real value 20 years ago and wouldn’t have been produced. Does that “not count” somehow?

I don’t think so. Value (once you get past food, shelter and safety) is doing the things we want to do. The “Amazon of thought” that is being built is allowing a whole lot of new things to happen, in a lot of new ways. I suspect that creative energy and demand is going to continue for a long, long time.3

1 Don’t come at me - I actually love bookstores and spend a lot of time in them and support them. But you have to admit, while they are wonderful, and good for discovery, they aren’t particularly efficient.

2 Though there are almost certainly opportunities to arbitrage cheaper/smaller agents that are going unused right now.

3 I don’t usually disclaim this but: this letter (and all of them) is really just my personal opinion, and not any kind of official Microsoft statement or position. This is just me, as a technologist and technology follower for 40+ years, remarking on what I seem to be seeing. Take it with a grain of salt.

What if Birds Invented the Airplane?

Section titled “What if Birds Invented the Airplane?”Or, Is AI Worth It?

Section titled “Or, Is AI Worth It?”

Birds, building an airplane, for some reason

One of the debates in the tech industry these days is whether coding with an AI assistant is “worth it”1. That’s not actually how the question is usually phrased though, since “worth it” is a hard thing to define accurately. Usually, it’s asked in terms of speed, which is a simpler question than “does AI make you more productive as a coder?” or even “Are new and more valuable things being done with AI that wouldn’t have been done before (like prototypes and other explorations)?” Even that question is complex though, as we will see.

I had a weird fantasy the other day: imagine if birds had invented airplanes. Think about this for a second. That’s a little like humans, whose main advantage is our brains, inventing LLMs, which can do some of the things our brains can, but work differently. What would birds say about airplanes? Are they “worth it”? I can just fly to that tree over there! What’s the point of a big, expensive, loud plane? You have to wait in line, it takes longer to get anywhere close! It breaks in novel ways that birds never break in! Needs all this fuel and infrastructure, look how expensive that is! Sure it flies, but if your wings aren’t flapping, is it really flying (thinking)? Look, if you turn the steering wheel a certain way, it crashes, birds never crash (well, except sometimes into those window thingys. Look! Airplanes even have windows ON them! Think how hazardous they are!)2 Most birds learn to fly quickly and that that, you have to train to fly an airplane and then it’s super hard to do well. It’s just not worth it!

But of course, there aren’t many birds who can fly across oceans, or can fly as fast as a plane. In our absurd fantasy, there would be uses of the airplane that even birds would find valuable - and perhaps they’d invent new migrations or societies with the airplane. And so on. Airplanes wouldn’t really be good or bad for birds - just different in value in different contexts. But it’s easy to imagine the “why not” stories birds could tell themselves if they felt threatened that something else could now do their core “value” of flying.

The confusion about code, and the absurd story of the birds with the airplanes is another example of our old friend, dimensional reduction. This is when we take a complex, multi-dimensional problem and try to reduce it to a single dimension so that it’s easier to talk about3. This pattern happens all over the place - more or less, any time someone is asking the question “Is A better than B?”, there is a possibility that it’s happening. That comparison, “better”, is a metric - and metrics only work in one dimension. It’s like looking at a red car and a yellow truck and asking which is better … well, it depends on whether you’re evaluating it as a truck or a car, or whether you’re evaluating by color. Maybe you want a red truck, and neither is “better” in that reduction!

We’re doing that here with the AI coding problem. We are looking at many different kinds of coding - new code, code in old codebases, frontend code, backend code, short little projects, long complex ones … there are a lot of dimensions to software. We are more or less discarding them to ask a single dimensional “is it faster?” question. Even if we broaden out to the question we really want to ask, “is it worth it?”, we are still in yes/no territory, and we’ve still had to discard some of that nuance to ask the question.

The real answer, of course, is “it depends”. And it’s even more complex because there are kinds of coding that wouldn’t have happened at all without AI - people who didn’t have the ability to write code at all, or tasks that wouldn’t have been worth the effort. You get a zero divide if you try to compare whether AI makes those “faster”!

To broaden this out a bit into other areas - we will wind up asking this for many domains soon. Code is just an easy one to start with because it’s something the models do pretty well right now, the tooling is well developed, and it’s measurable. But eventually AI will get “plumbed” into all kinds of things.

When we reduce these complex situations to single dimensions, we gain clarity and simplicity in the argument - we can talk about better or worse - and it feels more effective. But in fact, what we are doing is arguing about a summary or analogy, a reduction in information from the real complexity of the issue. This makes it easier to argue, but harder to understand and come to useful conclusions.

It’s frustrating to not have neat answers but complex situations actually need more complex dialog to understand. Think of the birds and the airplane!

1 Really the debate is whether AI overall is worth what we are investing into it. But coding is a little easier to wrap our heads around, and I think it’s the first really economically useful activity with LLMs, mostly for mundane reasons: code is all text and the tools are easy to access for an AI (e.g. GitHub and other command line tools). That “plumbing” problem will get solved for more and more domains over time, so take this whole letter as a specific instance (coding) that will likely apply more broadly.

2 You can really run with this analogy a long way. The crash example is a lot like people finding a single specific task that an LLM fails on, and then generalizing to “this is totally useless”, for example. I find that almost every time I hear commentary on LLMs now, if I translate it into “birds inventing airplanes” land, it sounds silly, at best.

3 I can’t find the quote right now, but I read a poem once to the effect of “this is is an age of miracles. Man can fly, but now the air smells of gasoline”. Everything is complex.

Has the Economics of Software Run off a Cliff with AI?

Section titled “Has the Economics of Software Run off a Cliff with AI?”Don’t Look down

Section titled “Don’t Look down”

Most businesses have only ok scale characteristics. If you make chocolate bars, you take in cacao (commodity), do a bunch of work to it, add some margin, and ultimately ship a product. Each product has marginal cost (the cacao). The only real advantage from scaling up is that fixed costs, like the cost of processing machines and distribution, can get amortized across more sales. But fundamentally, there is marginal cost to each sale, and the margins stay fairly low.

Software pre-internet already started to break that model. Programs had to be put onto disks and shipped in boxes, so there was still some marginal cost, but mostly once you built it, it was “free” to sell it. It’s interesting to note that the costs of distribution led to a business marketplace where things like feature scale or channel ownership mattered the most.

The internet broke that. Distribution is free (almost), so now it’s super easy to build once and ship as much as you want, and the market became global because there was almost no difference in cost to serve anyone anywhere in the world. The economics shifted to attention, and first-mover advantage and network effects started to dominate.

In both cases, though, the economics meant that it was worth paying a lot to software engineers. Programs were big and hard to build, speed and skill mattered, so paying an engineer a lot of money to build once and then ship many times made sense. Eventually, with billion-user platforms, it even made sense to pay huge amounts of money for tiny, incremental features, since any new usage easily made the money back.

But now…all of that has changed. Some kinds of software are much easier to build (vibe coding) and this circle will only expand. There is an incremental cost now to shipping AI based software (inference) - each new user costs money to serve, and that money is “used up” - the electricity to serve the inference doesn’t accrue in any permanent sense, it’s just consumed. There is also an emerging trend that the best engineers are starting to consume as much in inference costs do develop software as their salaries (sometimes even multiples - it’s not hard to imagine a world where the best engineers cost 10x their salaries in inference, and are expected to do 50x or more the work a single engineer can do today).

All of that is pushing software to look more like that chocolate company above, where there isn’t as much leverage from scale, where margins compress, and where the “line worker” (average engineer) isn’t that valuable. In fact, that’s a prediction I will make, that software companies, and the software industry, will come to look much more like manufacturing: a few highly talented engineers will plan and oversee complicated “factories”, and most engineers will be low-paid “line workers”.

Anything that is transient, easy to reach with vibe coding, idiosyncratic, etc, is likely to get squeezed hard economically. Engineers and product designers who can’t make effective use of AI to build economically useful software that can scale well will also struggle. The days of adding a small feature to a huge product are likely ending.

In the engineering teams I work with, I see a real bifurcation. There are hardcore engineers who disdain AI based coding. This group is, fortunately, getting smaller, but still doesn’t make much effective use of these tools. At the other end, there are product managers and designers who aren’t technical enough to use the tools. Neither of these groups is thriving or seems likely to.

In the middle, there are people who are some mix of creative and engineer - 60/40, 40/60, either is fine. Those folks seem really well positioned to make use of these new tools. They imagine interesting things, use the tools effectively, are constantly experimenting, and have high leverage. I suspect this kind of “product engineer” is what the future of software engineering will mostly look like.

I personally lived through the arrival of the internet as a coder. It was very clear to me that, to survive, I had to understand both the technical and business implications of that shift. AI is breaking the most fundamental assumption of software: that it scales at almost zero cost. This will absolutely change the dynamics of the whole industry, probably in unpredictable ways. It’s a fatal error as an engineer or product leader to ignore this challenge right now.

I never charge for these, even though people ask to pay. If you like them, please help me by sharing them. I just like to have people read them.

Where Are the Fast Takeoff Teams?

Section titled “Where Are the Fast Takeoff Teams?”And a Few Thoughts on Intelligence

Section titled “And a Few Thoughts on Intelligence”

One of the questions posed by tech industry insiders for the past few years is whether AI will have a “fast” or a “slow” takeoff. A fast takeoff means that AI itself becomes smart enough to accelerate its own development, and that feedback loop goes very quickly. It’s not an unreasonable concern - we’d like to keep control of our technologies, and we don’t always fully manage that even with non-self-improving ones!

It’s a tough thing to debate, since we can’t prove the negative (it won’t happen), and if the positive does happen, it won’t matter (because it’ll take off). But lately, it occurs to me that there might be a few things we could watch for that would be early indicators. And unless I’m wrong, I don’t think we are seeing either of them yet.

The first would be what I call “fast takeoff teams”. This is a team that is using AI based tooling in a compounding manner, or recursively. There are plenty of teams who are getting good acceleration in a linear way, where the “constant factor” of improvement is very high - they can do something in 10% of the time, say.

But geometric or exponential acceleration is different. It would look like “we built this tool that lets us get 2x as much done. Then we used the tool to build another tool that would have been hard to build, and that lets us get 4x done. That tool is so capable that it let us build this really hard tool we thought was impossible, and that lets us get 8x done. Now that tool is working on another one that we barely understand that we think will let us get 16x done…” That’s compounding, using the tools to build an ever-taller stack of ever faster tools.

It could be we are seeing this, and the exponent is more like 1.1 or even 1.05 instead of 2, so it’s not showing up quickly, yet. But I don’t hear much like this from teams - possibly some of the code generation teams are getting there.

The other indication we would see of a fast takeoff would be the training curve bending. The curves are very stable, and logarithmic - each step is 2x more expensive1, but intelligence (for some definition, see below), is increasing. Unless there is some unexpected breakthrough (possible, but again, impossible to prove or predict by definition), we should see that relationship begin to bend if the models are making significant progress towards making themselves smarter, or cheaper at the same level. As far as I know, we aren’t seeing that yet either (I could be wrong with both of these - I don’t exhaustively research the field).

There are lots of reasons this might or might not be true. Some of them are practical - models need to live in the real world enough to have real impact, and maybe we just haven’t connected all the plumbing yet, for example.

One thing that intrigues me though, is that we use words like “intelligence”, and “reason” as though they were well defined. Are they? Certainly, there are things we can build that are really “intelligent”, more than we are, in some domains - the trivial example is always the calculator, but almost any definition of intelligence has trouble excluding most software. That’s why you have to modify it with something like “General” when we talk about AGI.

The models we build are some kind of intelligence, just like all software is, at least in the sense of “can do useful things with information”. These are broader in some ways, and sometimes that breadth fools people into thinking they’re broader still. This is just an occupational hazard, just like we get emotionally involved with fictional characters on the screen and in books, we are experiencing the same confusion with these very powerful new tools.

It’s easy to look at what they can do, assume they can do all the rest of the things we can, and expect that they will be us, but faster and electric powered. And maybe they will, probably they will someday (the human brain uses roughly 20W of power, so there is clearly a long way to go, to improve on current LLMs). But right now, we don’t seem to be seeing the compounding we’d expect from a fast takeoff, and I suspect that’s because there are still some missing pieces (like iteration, experimentation, and more robust, continuously integrated and nonlinear memory).

Where is All the Collaboration in AI?

Section titled “Where is All the Collaboration in AI?”Also a Controversial Product Theory

Section titled “Also a Controversial Product Theory”

As one of the creators of Google Docs, it’s frankly kind of bizarre to me that none of the AI labs have built meaningfully collaborative threads yet. And the funny thing is - I know all of them use GDocs! They have the design right in front of them!

What do I mean by collaborative? If you share a thread now, what you get (last I checked) was a static copy you could read through. There’s no easy way for two humans to interact with an LLM agent at the same time.

But more than that, we’re missing the whole suite: attachments, permissions, forking, full coediting of all of the parts of an agent, etc. It’s weird. I think it’s at least partially rooted in the early idea that chatbots are some kind of search replacement. Search has a very binary idea of ownership - everything is either private or public to the world. There’s no nuance like a private folder with other people.

The search orientation also shows up in the idea that you interact with a chatbot in a very transactional way - come, ask a question, leave. There’s very little in the direction of longitudinal, collaborative project work. Environments where a bunch of humans AND an LLM talk about a problem for long periods of time, create artifacts, share data, have side chats, and get something substantial done together. Every time I build some kind of prototype in this direction, particularly with bots that have their own rich memory state, it’s much more powerful and interesting.

So it’s really weird that none of this has been done yet. Even just the most basic ACL-based sharing. Co-editing a thread is easy! It’s last in wins! There are a few interesting problems (like, does the LLM respond to multiple people at once, or act like a person and only have one “train of thought”), but come on! It’s not that hard and would be useful.

Here’s the controversial product theory: I think the industry has largely spent the last 15 or so years not building whole products from scratch, but building features on top of large, established products and platforms. I know lots of engineers at Google who spend all of their time adding one more feature to Maps or YouTube. Building a mobile app means mostly designing inside of a well-defined platform. Same with the web - everything is stacks and stacks of opinionated frameworks, and the end result is narrow and transactional.

Ok so grumpy old dude shouting at clouds time: I think this is causing an erosion in the ability of folks to think about product design holistically. You can see this with LLM design - again, that very transactional, feature-by-feature design process. Sure, lots is going on, things are changing quickly, but beyond fine tuning for specific things like coding, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of thought going into designing for use cases, complex workflows, composability and so on. Thinking of the product as a system and doing system level design.

It might be that this kind of thinking is just hard and I am mistaken. But it do find it striking that what seems to me to be obvious, low-hanging fruit on the product side of things (where it’s cheaper and should even be vibe-codable!) is going neglected.

Or maybe I just have sharing on the brain. 😂

Thanks for reading Sunday Letters! Sharing is kind of like collaborating.

Schemas Are a Hack

Section titled “Schemas Are a Hack”Well, at Least an Optimization

Section titled “Well, at Least an Optimization”(this is a bonus post for a friend who says I say this often but haven’t written it down)

What is a schema? It’s a mapping from the real world into some kind of regular structure that is usable by a computer. That last bit “usable by a computer” is the important bit - schemas, like many other things in programming, are a form of mediation between the complex, chaotic, messy real world and the binary, limited, deterministic digital one.

Schemas also help with performance. If you don’t have fast enough hardware, then organizing your data in a regular way lets you make use of optimization techniques like indexing, that make access and use much faster. This was the standard technique for decades - SQL and other forms of regular databases, and it’s still used extensively today. In many cases, being able to have a stable, structured format is helpful - not just for performance but also organization and quality control.

But the scale of the web taught us that schemas also start to break down at some scales. One of the new techniques invented in that era was “No SQL” - databases that didn’t have the same kind of regular indexing and structure of schema, but rather were focused on being able to scale large amounts of parallel access in a cost effective way. The mediation was now in the way.

Something similar is starting to happen again with the rise of LLMs. Part of what schemas do is to map the world in a predictable way. But they necessarily involve choices, and sometimes those choices are ambiguous. Is a hotdog a sandwich? for example. Forcing things into a schema is often the source of bugs and edge cases in more complex code.

LLMs are a different kind of mediation with the real world - a little more direct. Now the computer can mediate itself. If you ask whether a hotdog is a sandwich, you get a more complex answer1, one that can be tuned or used for different purposes. It’s less deterministic but it’s more flexible and possibly more useful.

Often in human culture, we form an adaptation to some limit, that then becomes accepted practice even after the limit is removed. Schemas are an example - still useful in many ways, but the original limits that led to them have evolved. Rethinking that kind of reflex is always a good thing.

1 I asked:

If you go by a strict structural definition—bread on two sides with filling in between—a hot dog qualifies as a sandwich. But most people treat it as its own category, the way a taco isn’t usually called a sandwich even though it’s food in a folded carbohydrate wrapper.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has even weighed in: for labeling purposes, they’ve called hot dogs “sandwiches.” Culturally, though, the consensus leans toward “no, it’s its own thing.”

So technically yes, socially no. Kind of like how Pluto is technically still a planet to some people, but not to the International Astronomical Union.

Now We All Get Money Disease

Section titled “Now We All Get Money Disease”

The gorgeous St Croix River in WI where I hang out sometimes in the summer,

Why do I write this letter, for the 5K or so of you who read it? As anyone who’s pledged money to it knows, I don’t take payment, and I just do it for my own reasons. I don’t have a personal or professional goal.

I do it for a few reasons. Partially because it helps me be more present in the moment during the week, looking for the kinds of patterns I might discuss here. But most importantly, I do it because it helps me think. There is something very different to writing out your thoughts, especially for others, than just sitting and musing. It’s hard, and you really have to confront yourself in an honest way. This is so valuable that two different people this week spontaneously said to me that they write for the same reason.

So what is money disease and what does it have to do with this? There are a lot of wealthy people in tech, and I know, personally, a handful of actual billionaires. They all have what I call “money disease”. You know what it is: they get isolated, even if they try not to. They can have whatever they want, life is pretty easy (so they work at making it hard), people around them tell them what they want to hear, even if asked not to. It’s very corrupting, and most of them gradually lose touch with the experience of being a normal human - all kinds of crazy lies that way.

I was talking to Alex Komoroske this week and he pointed out that we now all get to have the experience of being a billionare, with AI: it will tell us (more or less) what we want to hear, it’s very much a syncophant/echo chamber, we have infinite power over it and it’s infinitely servile. Yay! Now everyone gets to have money disease!

One of the things I like to say around here is that AI is not a person. It’s so easy to be fooled into thinking it is, that you’re talking to someone who is genuinely responding. Here’s a great illustration of that. The author shows how you can get ChatGPT to apologize for nearly anything, made up or not. It seems like it’s really a person - it has real contrition and seems to “learn” its lesson, but in reality, it’s just echoing your scenario.

Now imagine you are using a chat model to think, instead of doing real writing with real people. It agrees with you! Thinks you’re amazing! Riffs on the idea in plausible ways. But none of it is real feedback. You’ve fallen into the money disease pit, and you are slowly losing your ability to think.

When the internet happened, it was possible to think several things at once: that the technology was hugely important and would reshape the world, that most of what was being built with it was useless nonsense, and that it had hidden hazards that needed to be understood. The same is true of AI.

Writing is an important part of thinking. Letting the AI do our heavy mental lifting for us will give us all flabby muscles and disease, in our minds as it would in our bodies. As with all of our technologies, use it thoughtfully!

Thanks for reading Sunday Letters! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Do You Own Your Memories?

Section titled “Do You Own Your Memories?”You Really should…

Section titled “You Really should…”

How would you feel if, when you left a job, your employer could keep all of the memories of your work there? Real life Severance, right? That’s just science fiction. Except, it’s not - there’s a real danger that we are moving to a world of agentic software where your memories aren’t really your own.

One thing I’ve said around here annoyingly often is “bots are docs”. I started saying this for a different reason - because LLMs can’t keep secrets, no matter how well prompted, we need to store memories in a secure, separated way. Otherwise, your agent might tell a secret like your credit card info to a hostile third party. Fortunately, we already have a good mechanism for this kind of semi-shared secret: documents. Asking an agent to only disclose some of what it knows about you is a bit like telling someone only to read one page out of a long document that has all of your life in it - you’d never do that! We know how to separate and share documents.

But also - we don’t expect Google, Microsoft (disclosure: I work there) or Apple (or anyone else running a document service) to suddenly decide they “own” all of your documents just because those documents are hosted in their service. You have, and should have, an expectation that you can download that data, easily, any time you want - through APIs or other UX.

But with agents, we are in danger of building a very different world, where the providers of agents consider agentic memory to be their property, not yours. In a work setting, this is complex already, but we have some precedent - you don’t get to take confidential information with you when you leave work. But you DO get to build skills that you can use at your next job.

In a personal context, it’s different. There, it’s very clear that whatever you create with a digital tool is yours. That should extend to agents and what they output. If you work for months partnering with an agent on a project, you should be able to move those memories to a different platform if you want to - either to continue or to start a new project from that foundation.

The early days of online documents saw a lot of barriers erected to make it harder for users to move between platforms: weird text encodings, complex formats, etc. Ultimately, what this mostly did was slow everything down and make it harder for users and companies both to be successful. The web was a happy accident of open standards that gave us an absolute explosion of creativity and innovation. HTML and HTTP suddenly mean that anyone anywhere could write and publish to the whole world in an open standard way.

We need that for agentic memory. A world where a few providers lock up the skills and patterns you develop with your agents into their platforms is poorer for them, and for you. Bots are docs! You should have the same expectations for them that you do for your documents.

We Are Still Professionals

Section titled “We Are Still Professionals”Thoughts on the Future of Coding

Section titled “Thoughts on the Future of Coding”

A few thoughts on the future (and present) of coding.

The pace of AI-assisted coding is incredible. I tend to rely on historical analogies to understand the moment we are in, but even those fail to capture how rapidly things are changing. The expert practitioners are thinking very deeply about the nature of coding, how intention is expressed and transformed, what workflows work now, and more.

One historical analogy holds though: you have to be professional to build something that scales. (Maybe this will change, but for now it seems true). In the early internet era, it was relatively easy to put an app up - some HTML, a copy of Apache, and MySql, and you could be serving something. Lots of people who didn’t really understand the engineering built things that fell over as soon as they got just a little attention. But to really build something that scaled to millions or billions of users, you still had to do real engineering, had to really understand the technology, and sometimes invent some new tech too!

I hear similar things happening with vibe coding - people making changes to OSS projects that look good but don’t actually work, tests that aren’t really tests even though they have good coverage, etc. It’s true that it’s really easy to get something that looks ok quickly, just like it was easy to get a good-looking web site up, but there is still a need for professionalism, at least in projects that need to scale.

Interestingly, I can also argue a bit of the other side of this, but in a different context - if what you want to do is small, one-off, and doesn’t need to scale, just like with the web analogy above, it’s fine to just vibe it. I hear programmers talking about the lack of precision and repeatability in AI created code, and they’re both right and wrong. Users will just bang on the machine until it does what they want. If they’re building for themselves, it doesn’t matter that it’s funky or inelegant or even broken - as long as there are enough safeguards on the supporting systems so that data isn’t lost or leaked, it’s actually a very good thing to let lots of people create for themselves - that’s actually the larger lesson of the internet.

So - we have to not forget that we are professionals and need to do real engineering, when it comes to scaled, complex projects that AI can’t fully handle today, while at the same time remembering that letting lots of people make code that we absolutely hate is actually a good thing.

The media professionals that were displaced by the internet hated all of the slop that us normal folks made. But movies and books and high-quality media still get made, even as more and more “amateur” content is produced. And the amateurs are informing the professionals, showing both what can be done, and what is really valued.

Don’t lose sight of your professionalism but also, learn from and appreciate the new entrants who don’t need us as gatekeepers any more!

The Painting is not the Paint

Section titled “The Painting is not the Paint”Don’t Confuse Mechanism for Value

Section titled “Don’t Confuse Mechanism for Value”

No one would look at a famous painting and think “well, that’s only about 100 an hour (whatever), so it’s worth $500 (make up your own numbers).” Those things were certainly part of the painting being created, and they do have fixed value, but the real value of the painting is the idea, the impact, the art - however you want to describe it. We understand this - the mechanism isn’t valuable per se, it’s the outcome.

And yet…I see lots of folks in many realms that are being impacted by AI being caught up in the idea that the current mechanism is somehow inherently valuable and should be protected. Just to pick on my own industry for a minute, I see lots of programmers who are scared that the practice of writing code will be taken over by AI (true) and that they won’t have a job (false). ( I also see folks arguing the other side of this, amusingly - that even though AI will create code, because it’s currently not great code, that it never will be, and that “people reading code most of the time” will continue unchanged. I doubt it).

Code has always been a means to an end. If you want to be a bit more poetic, code is how we mediate between human intention and computer action. Programmers are the mediators, and code is the mechanism of that mediation - code plus some programmer judgment. But what really matters and is valuable is the computer action, the usefulness of whatever new thing we think of to have computers do. The code of a web page isn’t really that valuable, the fact of a connected internet of them is.

That mechanism of mediation (there’s a fun phrase - I seem to be in full nerd today) has always been evolving, as the capacity for software and hardware has changed. What we can do with computers has changed as processors have gotten faster and more connected, as devices have gotten more portable (and connected to sensors like cameras). Much of what we do now with our devices and software wasn’t possible at all when I started in my career 35 years ago.

This will be true for other fields as well. Often the practitioners of the field are highly trained in some specific mechanics - accounting, law, specific creative tools, etc. That skill is valuable, and often we charge for the time it takes to operate those mechanisms, because that’s convenient, but the mechanism itself isn’t we pay for. We don’t pay lawyers to produce words, per se, we pay them to produce results. We don’t pay a doctor to read a report, per se, we pay for their judgment and help getting to a medical outcome.

In my own career, many of the things that only a small number of people could do, like write code, have gotten easier. The market has expanded, and there is more value in the world. It’s meant that I have had to adapt and learn as the tools change, but that’s ok. It also means that the world is more inclusive - better tools mean that more people can get to the value than before. I can’t draw at all - it’s really nice to have tools that can help me express myself that way, for example.

We are richer and better, I think, the more that human creativity and intent can be expressed into actions. That intent will always be mediated into action, and those mediations will always change. It’s good to remember that the mechanism is not the outcome, the painting is more than just the paint.

AI is Worse, Which is why it Will Win

Section titled “AI is Worse, Which is why it Will Win”

One of the challenges programmers and engineers have is predicting which technologies will succeed. Engineers tend to look at things through the lens of, well, engineering. So, we have long, arduous debates about technical merits and minutia. We pick through (and cherry pick!) examples, discuss edge cases. In the case of AI, we run evals, plot graphs and endlessly debate whether AI is useful (it is) or a scam (it’s not). And folks not in the industry stand by and scratch their heads at it all, trying to decide if AI is a big change that will disrupt their lives (it will).

None of this matters as much as sociology (disclaimer, I am not a sociologist, and a friend of mine who is reads this so I have to say that!). Way back in the depths of time (40 years ago!) a debate like this was raging about why Lisp, which seemed “better” on technical merits, was losing to C, which was “worse”. The paper was called ‘The rise of Worse is Better’ and it’s still one of the best things ever written about the dynamics of how technology succeeds or doesn’t.

The core premise is that there are three things in any technology that are in tension, and you can’t have all of them: simplicity, completeness, correctness. You can have about one and a half, maybe two if you’re really lucky. And the answer, which I love because it fits so neatly with my thesis that “Users are Lazy”, is that tech that is Simple first but not fully Correct or Complete, will beat something that strains to be Correct and Complete but leaves Simplicity to whatever can be done after that. People are lazy.

The internet is like this. HTML isn’t really a great way to lay out a page, for a bunch of reasons. Word processor people I knew back at the start of the internet would say things like “you need real page layout, SGML (which HTML was derived from) is better”. But SGML is a huge, complex, brittle spec - complete and correct, but much less simple.

AI is Simple. Talk to it! It does stuff! It’s not complete (it doesn’t do all stuff), and it’s not fully correct (it makes mistakes, makes things up, can’t do everything a person does). Hopefully both of those reduce over time, but right now, for many tasks, AI in the form of LLMs, is simpler.

That’s why it will succeed as a technology. It’s possible there could be business model issues that prevent this (I doubt it - we have a long historical record of how optimizations work, and LLM tech is already way ahead of the typical curve, so I think it’s already clear that costs on current models will come down enough for them to be great businesses, even if they don’t get any “better” from here). But it’s already simpler to use for many tasks, and that’s why it’s spreading so quickly. This is also why the chat interfaces have spread faster than things like the API playground that came before it - chat is easier to understand.

Is it worse, or better, if you share?

Saying “AI is worse” isn’t a judgment on the tech or its value. Of course, we want the best technologies we can have. Worse is better speaks to the social and practical dynamics of how technology is adopted. Technologies with a certain pattern - simple to use over complete and correct - tend to win over time. AI fits that pattern, and we can see that in how it’s being adopted. And this is why many of the criticisms of it miss the mark.

AI Coding is the New Blogging

Section titled “AI Coding is the New Blogging”The Supply of Code is Going to Explode

Section titled “The Supply of Code is Going to Explode”

If you are my ancient age (58), you remember what the world was like before the internet. There were a small number of gatekeepers to pretty much all media: a few TV and radio stations, newspapers, and maybe for art, museums and galleries. If you wanted to publish something, it got progressively harder the more people you wanted to reach. You had to get through a gatekeeper, sometimes many of them.

Then the internet showed up. In theory, you could instantly publish anything on the web without asking permission, and the whole world could see it. In practice, that required a bit of technical skill - a web server somewhere (pre cloud! Often these were under someone’s desk) and an understanding of HTML to make a page.

Then tools like Blogger showed up. Suddenly, anyone could, shall we say “vibe publish” anything they wanted to the whole world. Now it seems quaint, but at the time, it was shocking. Suddenly all the gatekeepers were disintermediated, one of the favorite words of the time. This generally started an avalanche of other apps that let people create and consume content - YouTube, Twitter, FaceBook, you know them all. Now we are in a world of huge content abundance. Content is cheap, and attention is what matters1.

Now let’s look at software. Right now (well, until recently at least), there was another gatekeeper if you had a good idea that involved software: the engineer (or if you were an engineer, the time to do the work was significant and a gatekeeper of sorts). Now, it’s easy and getting easier, fast, to create code and applications with AI. Code is becoming very abundant.

In the historical analogy, I think we are roughly in the period where Blogger first showed up. The technical barriers have been removed and, if you are familiar with a fairly friendly but somewhat limited tool, you can get a lot done on your own. It’s safe to assume that those tools are going to get much friendlier, very fast.

It’s going to get easier and easier for ordinary people to go from idea to working code/tool without understanding much of the process, just like it’s gotten very easy to post an image or a video on the internet, something that required a lot of technical expertise and money just a few decades ago.

What does this mean for software? Well, for sure, there’s about to be a lot more of it, and a lot more people doing really creative things that involve code, where, often, they don’t really even think of it that way. Lots of interactions with computers, more complex data analysis, custom interfaces, and so on. It’s hard to predict - going from Blogger to YouTube even is a jump, going all the way to things like TikTok crazes is even harder to see.

If you were in “old media”, you got hugely disrupted, and this will likely happen to “old coding”. But not everyone did - there were tons of new opportunities and businesses to be made. I fundamentally believe that humans are the source of creativity and invention, and that gatekeepers, while often well intentioned, usually do more harm than good. So, I’m happy to see more tools in more hands being more creative, even if it means I myself will be pretty disrupted. Invention, persistence and creativity are what is going to matter now.

In 1990, almost every programmer was a “desktop” programmer. In 2000, probably fewer than 10% were - but we had a LOT more programmers. Everyone in media worked in “legacy” in 1990, and many of them didn’t in 2000, but there were a lot more creators and a lot more money in the system. This is likely to happen, as we shift to from yolo to vibe to lego to … whatever comes next (and this is maybe a topic for next week - we are, I think, seeing a new coding paradigm emerge, the way that Agile emerged from the cloud).

Vibe coding is the new Blogging. It’s still a bit early, the tools aren’t perfect by any means, but it’s getting easier all the time. Things built with code are about to be very abundant. The economics are going to shift from scarcity to abundance. Everyone can be a creator, and there will be all kinds of new jobs and opportunities. They won’t look like the old ones, but that’s ok.

Code is about to change, a lot.

When you share a post, some code gets its wings.

1 I asked Claude to do some research on how much more content there is now: In 1980, the amount of content created annually was limited to thousands of printed publications, broadcast programs, and physical media distributed through centralized institutions like publishing houses and television networks. By 2020, this had exploded to over 64 zettabytes of digital content (equivalent to 64 trillion gigabytes), with approximately 4 million books published annually, 720,000 hours of video uploaded to YouTube daily, and billions of individual creators contributing to an unprecedented democratization of content creation across multiple formats and platforms.

This represents an increase on the order of 10^6 to 10^7 (1 million to 10 million times) more content being created annually. Even if we only consider structured content like books, we’ve gone from tens of thousands of professionally published works to millions of books plus billions of social media posts, videos, and other digital content.

Man Vs Machine

Section titled “Man Vs Machine”Why It’s Still a Mistake to Think of AI as People

Section titled “Why It’s Still a Mistake to Think of AI as People”

As a middle-aged guy, one of my hobbies is shouting into the wind for no particularly useful reason. My current obsession on this front is the idea that everyone seems to have, that LLM-based AI systems are “people” in some sense. I know, it’s an easy shorthand, and they really seem to behave in person-like ways often enough. If your hammer softly wept at night because it was lonely down on the workbench or told you “You really hit that nail great!” every time you used it, you’d probably anthropomorphize it too.

But this is just our natural pareidolia fooling us. Humans are adapted to understanding the inner state of each other - it’s critical to our survival as a species, and what makes us special. So it’s a huge vulnerability - we can’t help it. Really though, a better way to think about these systems is something like “cognitive engines”: something that can process the information given to it in really complex and useful ways, but which is still, fundamentally, a designed object (at least for now).

Here’s a subtle example. You, and everyone, and every biological system you know, have a survival instinct. You have to, this is the most important thing in a selective system like evolution: if somehow you get a genetic mix that doesn’t produce a survival instinct, those genes are highly unlikely to be passed on. So, it’s very much universal that every biological system has this behavior.

It’s natural then to project that onto LLMs. They must have a survival drive! If we make them smart enough, they’ll take over the world! Etc etc. But these are designed systems, not evolved ones (even if the design process, training, is opaque and sometimes has some selective aspects). Designed objects don’t necessarily have to have survival instincts the way evolved ones do (though it’s possible to design those in, or to use evolutionary/selective processes to build them).

Think of other complex designed objects in your life. Your car doesn’t have a survival instinct. We might design some behaviors into it, like crash avoidance or anti-lock brakes, but those are designed. We don’t say “the car wants to live!”, we say “the collision avoidance system worked”.

Why does this matter? Analogies are only approximations, by definition, and they’re only useful as long as the approximation doesn’t stray too far from reality. Thinking about these systems in human-like terms tends to lead us out of the useful area and into mistakes in how we use, build, and predict them. AI’s have behavior and risks, sure, but we won’t understand them well if we think of them as people. Asking harder, getting frustrated, or explaining slowly won’t work. I see people getting totally lost in this idea, things like “AI should be paid for with headcount”.

The cool thing about these systems isn’t that they are just like people, with all of the same limits and challenges. The cool thing is that they can do some kinds of thinking, with machines, that we couldn’t do before, and because they’re machines, we can do really novel things. You can’t have a person try a task 1000 times in parallel, or ask them to check their work without bias, or interrupt them, or control them with code to perform a specific way, and so on. Thinking of these systems as programmable tools is so much more useful than thinking of them as fake people. As thinking machines, they’re incredible. As faulty quasi-people, they are flaky and scary.

Click here if you’re a real person

One of my core principles (that I learned from one of the best coders I know) is “don’t lie to the computer”. It never ends well when you lie to the computer when programming. Understanding the problem clearly and dealing with it honestly always works better. Thinking an LLM is somehow like a person/agent/whatever is lying to the computer.

It’s not Your Friend, It’s an API

Section titled “It’s not Your Friend, It’s an API”Why I Don’t like the Word “agent”

Section titled “Why I Don’t like the Word “agent””

I think there is a very subtle thing going on when most people (at least most lay people or non-AI researchers) think and talk about building software with LLMs. We tend to anthropomorphize these models because it feels right - we are having “conversations” with them, they are “agents” doing things “for” us, they “think”, etc. We think of them as “people”, literally, and subconsciously. It’s understandable - this technology does do a great job of simulating a human mind in some ways (don’t ”@” me - I’m not saying in all ways, I’m not saying perfectly, and I’m not saying they are human), can hold reasonable sounding conversations for long periods of time, and can often (not always but often) do real work and real thinking that is really impressive. So, it’s really easy to slip into the trap of thinking they have emotional state, “desires”, “tiredness”, and other human properties. To be polite. To think in terms of persuasion and other social aspects, instead of approaching them as engineering systems. (And when I say “them”, try not to hear it as “a group of persons”, but as a group of objects and systems. The language doesn’t work well for us here).

This infects our use of these systems in lots of ways. If you had a person and you wanted them to do a task, you’d a) assume some competence and grounding that isn’t always present in an LLM, b) ask nicely, or at least feel like, once they “understand” the request, they’ll “do their best” to perform it, and ask for help if they can’t, c) assume you are both working from some basis of “trust”, d) not do weird things like ask them 10 times to do the same thing, or ask them for an answer and then turn back around and break their answer into 10 pieces and ask them to check each one separately, or ask them to do a really huge amount of work (answer 1000 questions) on a whim, that you might throw away.

But these are things we do all the time with API calls: use scale, call it lots of times if we need to, do speculative computation, complex structures like MapReduce, and so on. We use them as tools in larger and more complex systems, we use them without feeling, however the engineering task at hand needs them to be used, and the idea of feeling “guilty” for using (or abusing) a service API call is absurd! (we might care about wasting resources, or it might be impolite or even DDOS to slam a service endpoint, but that’s it). Most folks aren’t quite explicit about this, but if you look, you’ll see these assumptions all over the place. People tiptoe around LLMs, instead of treating them like the stateless, emotionless API calls that they are. The language used often betrays this subtle way of thinking about these systems.

There’s also something some people try to do with an LLM that we wouldn’t do with an API call: trust it to keep secrets. If you ever think “I’ll set up the system prompt to not divulge secrets”, or any other kind of “social” “persuasion”, you’re doing it very wrong. Back in the land of an API call, we understand that if we pass a piece of information to a third-party API, we have no idea at all what happens to it - it’s now public, in the wind. And yet, many “agent” designs and other products I see seem to have implicit assumptions that if we somehow “convince” the LLM to be trustworthy, we can trust it with secrets, like a person. It’s not a person! It’s an API call! (I get excited)

The other reason I think this is important to call out is the very broken conversation about intelligence, AGI, and so on. Lots of folks look at LLMs through the lens of “is it as smart as a person yet?” We don’t do this for other services - we just use them! We don’t think “yeah, cloud database of choice is really good at remembering things but it’s not good at jokes yet, what a disappointment”. What we actually do is understand what that service is good for, and build it into an engineering system that does something useful.

So many people seem to be swinging for the brass ring of “magic thinky box that does everything”, and missing lots of “wow, I can use this tool to trivially build something I couldn’t before”. Even things that are much narrower than “general purpose human intelligent agent” can be really, really valuable. My team calls this approach “metacognitive recipes” - mixing code (the metacognition - planning, correction, self-testing) with inference in useful ways. A long time ago (in AI land - two whole years!) when the models weren’t very capable, and token contexts were small, and everything was slow, I tossed together a Jupyter notebook with 5 simple prompts I called “the textbook factory” - very reliable way to use 600 or so API calls to produce a textbook for any course, any level, full year, teacher’s guide, etc. You might be able to get an advanced model to do that now with one prompt but then - no way. And I’m sure that there are things we can do with more advanced models now where 1000 or 10000 calls in the right structure are way more useful than what most people are doing, for the right problems, thought about the right way (and I have LOTS of ideas).

And these calls are getting really cheap! DeepSeek R1 is something like 150K or so) you can generate a novel’s worth of thinking for every record in a 10M record database! Do you think “gee I wish I had a stadium full of these agent fellows I could do that with”? No, that’s silly! But it’s much easier to think “OK, I am going to work out this technique, and then I can make 1K of API cost? 10? What kind of speculative things can you do if you can look that deeply at all of the <documents, data, communications, events, logs, build process, etc> in your company? It’s a tool, think of it as engineering, not conversation. Write software!

They’re not your friends. They’re not secret agent man. They’re not people. It’s an API call with really useful tech behind it that can usefully do things in the semantic realm that we couldn’t do with code before.

See the tech for what it is and build useful things with it!

The pace of Change, Agents, and Hallucinations

Section titled “The pace of Change, Agents, and Hallucinations”

A while back I wrote something about how it’s much easier to elaborate on an idea once you have it, then to know where to look in the first place. This can be said as “0 to 1 is hard, 1 to many is easier”. We’re really starting to see this impact in the AI world.

A year ago (plus a bit) there was only 1 “GPT-4” level model, and it wasn’t clear how hard it would be to build another one. Now there are dozens. When DeepSeek came out with theirs in December, with a training cost three orders of magnitude lower, I thought “huh, if we get another three, then you can make one for about 450 in training. Four orders of magnitude, not in a year but in a week! Things are moving fast.

Related to this, I think there is a huge gap between what is possible and what people are doing. Inference costs and latency are coming down very rapidly and will likely continue to do so. Are there solutions to hard problems out there that we can get to just with brute force? When I look at the hallucination/error problem, it feels a little bit like distributed service reliability. In that world, reliability didn’t come from making the hardware never fail (which is sort of like making the LLM never hallucinate in my analogy), but by managing failure gracefully by adding a software layer and redundancy. What if we can do that with inference - does a lot of checking eliminate errors? Is it like uptime, where you can get more 9’s but each one costs exponentially more, and there are never any perfect guarantees (so, we can get fewer mistakes but never 0, and the higher accuracy costs much more in extra inference)? Or the example from last week - what can we usefully do by throwing a lot of inference at harder data analysis problems? Are there regular processes that your company has, where humans do a lot of debate, that can be streamlined by having the models work on them?

One last thought for the week. I’ve been contemplating the idea of agents a bit. One thing that bothers me about the current dialog is that it violates one of my principles of product design, which is “don’t break faith with the user”. That is, if you present some model of how your product works, it should stay faithful to that model. Don’t lie to the user, in other words.

“Agent” makes a promise it can’t keep: that the AI system is a person. It’s not - it’s a program that does a good job of imitation the behavior of people, but it is missing all kinds of pieces like memory, continuity, self-awareness, and, actually, agency. The problem comes when a user understands and accepts this kind of idea, depends on it, and then is let down by missing behavior. The ambition is great, and “it’s just a person, talk to it” is a really compelling model because it’s so simple, but it never ends well when we lie to users like this.

It’s tough to build products when the world is moving as fast as it is now. Stay focused on user value and understanding, and don’t forget to experiment and make some messes - there are so many new things to try now.